From Unidentified Political Object to European Democracy

Thirty years after the foundation of the European Union by virtue of the 1992 Maastricht Treaty the nature of the Union has been established at last. At the time of its creation as successor of the European Communities the EU used to be described by the then President of the European Commission Jacques Delors as an ‘Unidentified Political Object’. At the start of the Conference on the Future of Europe three decades onwards the author of the present blog suggests that the EU has evolved to a European democracy, which may be identified from the global perspective as a ‘democratic regional organisation’.[i]

Deadlock

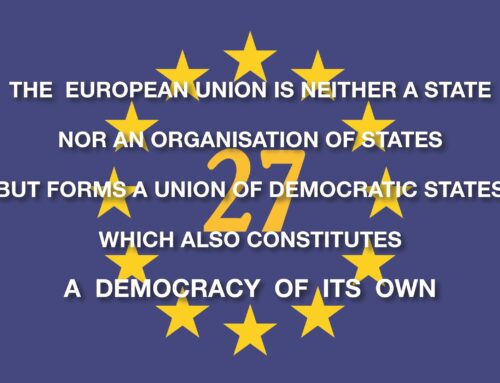

The line of argument is as transparent as convincing. According to conventional wisdom, the EU should either be a state or an organisation of states. Other options are not available. However, the EU is not a state because it does not aspire to be a sovereign state. The EU Court of Justice established in its Opinion of December 2014 that ‘the EU is, under international law, by its very nature precluded from being regarded as a state’. In consequence, the EU has never applied for membership of the Organisation of the United Nations. This conclusion does not imply that the EU should therefore form an organisation of states. It is not, because the Union is also composed of citizens, has an autonomous legal order, a directly elected parliament, a single currency as well as an autonomous democracy. So, the conclusion is unavoidable that the EU is neither a state nor an organisation of states.

Towards European Democracy

The fact that the European institutions and the academic community are unable to identify the nature of the EU does not mean that the Union should not exist. There is no point in denying reality in the name of theory! It is neither feasible to organise an ambitious and time demanding conference on the future of the EU, if there is no theoretical foundation for the functioning of the Union. To put it simply: the European Union cannot solve its existential problems by ignoring them.

This observation is the more compelling in view of the inclination of subsequent European Commissions to describe the EU in terms of a European democracy. In his Political Guidelines for the Next European Commission, published in July 2014, its newly elected President Juncker accentuated his view on the EU as a Union of democratic change. Pursuing the same line of thought, his successor Von der Leyen vowed in her Agenda for Europe of July 2019 to give a new push to European democracy. This priority has found expression in the European Democracy Action Plan of 3 December 2020, which aims to ‘empower citizens and to build more resilient democracies across the EU’.

The theory of democratic integration

As EU citizen, the present author intends to contribute to the success of the Conference by suggesting to substitute the civic perspective of democracy and the rule of law in the study of the EU for the traditional paradigm of diplomats and states. According to the Westphalian system of international relations, as the latter is known, the concepts of democracy and international organisations are incompatible. Democracy can only thrive within the boundaries of a sovereign state, whereas the relations between states are the domain of diplomacy. Hence, international organisations are by definition unable to function on a democratic footing. So, if the EU wants to be a democratic union of states and citizens, it must replace the traditional paradigm with a new perspective. The theory of democratic integration intends to do just that by studying the EU from the citizens’ point of view. The new theory holds that, if two or more democratic states agree to share the exercise of sovereignty in a number of fields with the view to obtain common goals, their organisation must be democratic too.

New Horizons

Swapping paradigms opens new horizons for the EU. The EU is no longer destined to repeat the past but may determine its own future as a post-Westphalian polity. It can recount the story of Europe as a deviation from the traditional paradigm, in which the conduct of war was seen as a ‘natural’ phenomenon. By sharing the exercise of sovereignty, the participating states not only succeeded in replacing war with the rule of law, but also increased the prosperity and well-being of their citizens. The theory of democratic integration explains why the Communities, which were identified by the European Council in 1973 as a ‘Union of democratic States’, were poised to acquire democratic legitimacy of their own. It describes the stages along which the evolution to a democratic Union took place, thereby characterising the present EU as a ‘democratic Union of democratic States’. Moreover, it gives the EU a new horizon at the global level by identifying the Union as the first-ever ‘democratic regional organisation’. The Conference offers a long-awaited opportunity for the EU to realise its potential and to prepare itself for the 21th century. The theory of democratic integration is here to serve the EU as a philosophical foundation for its functioning as a European democracy!

Footnote:

[i] Jaap Hoeksma, The European Union: A democratic Union of democratic States. Free download at www.wolfpublishers.eu/futureofeurope

Photo credit:

© European Union, 2021

Photographer: Nathalie Malivoir

Comments on “The European Union: A democratic Union of democratic States”, by Jaap Hoeksma

This detailed contribution the “Conference on the future of Europe” attempts to provide a way forward in the stalled debate between a federal and an intergovernmental EU. It posits that the nature of the EU constitutes a new type of organization that no longer fulfils the criteria of the Westphalian model of statehood but creates a new paradigm characterized as a “democratic Union of democratic States”. The new theory holds that, “if two or more democratic states agree to share the exercise of sovereignty in a number of fields with the view to obtain common goals, their organisation must be democratic too”.

If this theory is to be upheld in the case of the EU, it becomes necessary to specify from the outset whether this objective has been reached (as suggested by the author when he explains that new paradigms become apparent only after their implementation), whether the objective is only partially met (as suggested by the declarations contained in the successive Treaties or ECoJ rulings and by the imperative needs to do away with the Members veto or the obligation to reform the electoral code of elections to the EP, etc.) or whether at present the EU does not yet meet the required standards to be considered a democratic organization. Reading the essay, I find that all three of these interpretations are put forward at different times creating confusion. I tend to believe that the EU does not yet meet the required standards to qualify as a democracy.

Another problem that stems from agreeing to share sovereignty in a number of fields does not answer the question of the treatment of areas that imply both the shared and unilateral exercise of sovereignty. For example, it is stipulated that “national” and “EU” nationality exist side by side, the conferring of nationality by a Member State (a sovereign prerogative) conferring automatically EU nationality. The “sale” of nationality by some Member States or lax conditions to qualify could gravely impair the interests (and sovereignty), not only of the EU but of other Members too.

Another major difficulty results from the application of the new paradigm to the external relations of Member States with third parties which remain within the traditional Westphalian paradigm. If the author recommends the introduction of majority voting in carrying out “foreign policy” as a shared interest, how can this be separated from applying the same concept to defence and security matters? Is the simultaneous existence of the status of enhanced “observer status” conferred on the EU, compatible with the full membership of Member States in organizations such as the UN, the IMF, etc.? Does the EU represent at the G7 or G20 all Member States or only those not directly represented? Are these variable geometric structures compatible with a democratic Union or should there be a strict hierarchy of norms and an agreed subordination to the principle of subsidiarity?

The author mentions briefly the possibility of Members withdrawing from the EU as exemplified by Brexit. He also mentions the “successful” sharing of sovereignty in the deployment of the €. Is it really conceivable that in a “democratic union of democratic States”, Germany could decide unilaterally to leave the EU (and the €) knowing that this would inevitably collapse the EU?

It seems to me that the value of the author’s contribution is to explicit the importance of substituting the broader civic perspective of democracy and the rule of law in the study of the EU for the traditional paradigm of diplomats and states.

In conclusion, is it not true that, if sharing sovereignty in the areas needed to deploy a robust “democratic Union” was achieved, the result would necessarily be – by construction – tantamount to a “Federal Europe”!

Thank you for your critique on my blog about the identity of the EU as a new subject of international law. You and I will agree that dialogue is a precondition for making progress, especially when you are entering -as we do with the EU- a terra incognita.

In view of your appreciation for the proposed paradigm swap, I presume that we also share the view that we need to reconsider conventional wisdom. For me, the identification of the then Communities by the European Council in 1973 as a Union of democratic states serves to illustrate the need for this exercise. Applying the traditional paradigm of the Westphalian system, the two prevailing schools of thought could both interpret the Declaration on European identity as testimony in favour of their argumentation.

Seen from the civil perspective of democracy and the rule of law, however, the 1973 Declaration forms the starting point of the democratisation of the EC/EU. In the subsequent Declaration on Democracy of 1978 the European Council emphasised its intention to give the ‘Union’ democratic legitimacy too. Transforming a regional organisation of states into a transnational democracy, however, takes commitment and perseverance. It has never been done before and, as you suggest, we are still in the midst of the process. So, you are right in pointing out that the EU has not yet matured as a European democracy. Against this background, I am grateful to have received the platform from the Federal Trust to propagate my views and discuss them with you.

At the end of your critique you raise the question as to whether my line of thought must ultimately lead to the conclusion that the EU will/must become a federal state after all. The fact that we disagree on this point, may make our exchange of views the more interesting. It brings our discussion back to Immanuel Kant and his Zum Ewigen Frieden. He suggested that states wishing to attain perpetual peace, might either merge into a federal state or form a confederation of free states. I posit that a democratic regional organisation is a new form of international organisation, which Kant could not have foreseen, but would have welcomed wholeheartedly.