Hard Brexit: Passport to Nowhere for British Services

With grateful thanks for assistance from E.Piciocchi, J.Kuozas & E.Manias.

October 2018

“We’re on a road to nowhere

Come on inside

Taking that ride to nowhere

We’ll take that ride…

….They can tell you what to do

But they’ll make a fool of you and it’s all right

Baby, it’s all right

We’re on a road to nowhere”

Songwriters: Chris Frantz / David Byrne / Jerry Harrison / Tina Weymouth: Road to Nowhere lyrics © Warner/Chappell Music, Inc

PRESS RELEASE (pdf file)

DOWNLOAD THE PAPER IN PDF FORMAT (3MB)

Executive Summary & Introduction

Passporting is a fundamental way in which the EU does business. It defines an important set of benefits open to members of the EU, and passporting rights are not generally made available to 3rd party states. The UK will become a 3rd party state after a Hard Brexit, and hence lose almost all of these advantages it currently enjoys with the EU.

Passporting issues were virtually ignored in the Brexit referendum debates, and have only surfaced relatively recently as the truth has dawned that new institutional arrangements will be required post Brexit, and business will not be “as normal” in a post Brexit future.[2].

In a Services Slump scenario, constructed after detailed analysis of the air, and land transport sector, as well as the financial services sector, the loss of passporting rights will be painful. It is estimated using an Input-Output approach, that solely as a result of weakening output in these three industries, overall national gross output could fall by over 6%. Regionally the brunt of the adjustment will fall on London and the South East, which will become the worst affected parts of the UK. When this is combined with the results of earlier studies looking at the impact of tariffs and restrictions on the flow of goods, double digit falls in output nationally would appear to be possible.

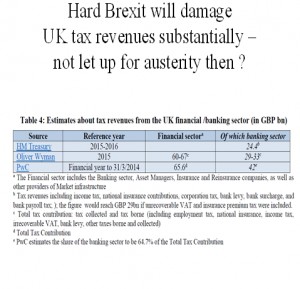

Losses of passporting rights will negatively affect the financial sector, itself a large contributor to tax revenues. This could lead to a reduction of around £20 billion a year in tax revenue, seriously complicating the government’s policies regarding financial and fiscal stability. No Brexit Bonanza has been identified, and the government appears to have no fiscal room to provide additional counter cyclical support for the UK service and other sectors. To achieve this, the government would either have to raise taxes, or increase borrowing. Both of which cross its own electoral “red lines”.

The results of this analysis strongly suggest that a Hard Brexit is effectively a passport (road) to nowhere. Either continued membership of the EU, or becoming a member of the EEA, or in negotiating similar arrangements as with Switzerland, would all appear to be more economically beneficial than the current Hard Brexit course.

Contents

Executive Summary & Introduction.

What the structure of EU service passports tell us about the EU ?.

Where is the Brexit Bonanza ?.

The Importance of Services for the UK Economy.

Current EU/UK arrangements for Air Traffic.

Financial Services and Passports.

The legislative underpinning of passports.

How large is the dependency on the EU ?.

Summary: Hard Brexit Impacts on Service Sectors.

The meso sector impacts of Hard Brexit on Services in the UK economy.

Regional Impacts of Service Slump Scenario.

APPENDIX 1: LIST OF EU AGENCIES.

Introduction

This report examines some implications that a Hard Brexit might have on UK government spending and future tax revenue. It finds that any potential fiscal gains are going to be more than offset by additional costs to be paid by the government, as well as losses arising from reduced output in various service industries, as well as costs related to the introduction of tariffs between the EU and UK (dealt with in previous papers).

It will examine:

- The loss of passporting rights in the financial sector, and the consequences of moving the Euroclearing operations out of London and to Frankfurt. There are further concerns of the future of commercial investment banking (CIB), as well as for Asset Management (AM) and Insurance/Reinsurance (IR).

- Loss of passporting, and the threat of relocation for corporate and investment banking, asset management, banking and insurance. This suggests that while corporate outcomes may be poor, they may be better than national outcomes. Relocation by companies and the establishment of new subsidiaries will lead to a transfer of financial services business out of the UK, in order that these firms continue to benefit from the full use of intra EU passports. .

- The potential increase in bureaucracy on international borders, particularly land borders, that will slow down the throughput of commercial vehicles to and from the EU, with negative effects on downstream industries. It is likely to lead to higher costs of business, increase working capital requirements, and damage complex just in time delivery systems.

- The problems caused by the loss of passporting rights for air transport. This is likely to result in the removal of a number of “freedoms”, much of which underpins the operations and profitability of air transport.

- The necessity of negotiating directly with EASA in order to maintain commercial flight connections with the EU.

- The loss of various governmental functions and deeper contacts with the EU. Their substitution by markedly less efficient and more expensive national government agencies. This raises issues around even handedness, and tendencies to favour the more powerful national organizations over smaller competitors

These frictions represent various forms of non-tariff barriers, and are likely to be more persistent and long lived than issues around tariffs on goods, although the international climate on tariffs has deteriorated recently leaving a post Brexit UK more vulnerable to trade and tariff wars with existing trade partners.

Progress in international relations in improving access for service providers has been painfully slow. The EU stands out as an exemplary case of how completing the single market, not just in goods, but in services too, is streets ahead of practices elsewhere in the world. And it can be said that this is in no small measure due to the activities of earlier generations of Conservative politicians and policy makers, many of whom followed Mrs Thatcher’s demands that the Single market should be completed, including the removal of barriers to the intra EU trade in services. With a Hard Brexit, the UK will be effectively excluded from all of these benefits.

After taking a close look at these issues, estimates of likely costs will be made. These in turn will be used in our UK Input-Output sector and regional model to provide estimates of output losses that could arise in the case of a disorderly Brexit, referred to here as the Service Slump scenario.

Chequers and the Dodo[3].

Before embarking on a dive into the details of passporting, it is useful to understand how the current negotiations between the EU and the UK appear to have reached such an impasse. One of the difficulties with the Brexit negotiations from the British side has been the problem of “being in government, but not in power”[4] . In 2017 the government’s weak, but probably sustainable position was gambled away by the Prime Minister in a display of great over-confidence. Having won both the earlier Brexit and Scottish Independence referenda, as well as a General Election, it was thought that one final “shove” would demolish what was left of the Labour party opposition, and cement the Tories in power for decades to come.

Instead, the government lost its overall majority in the House of Commons, and had to form an uncertain alliance (marriage of convenience) with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), itself unable to form a government in its own backyard at Stormont in Northern Ireland. Worse was to come, since the Tories have suffered for years from a strange fixation with Europe and the EU, and a desire to leave it as the earliest opportunity, according to some Brexiteers, at any cost, however unreasonable.

The higher echelons of the government around the Cabinet and in the civil service were, in many (but not in all) cases aware of the broader situation, and the degree to which on the economic side, the country was now deeply part of the network of relations, agreements, laws, directives and protocols binding the EU member states together. These are, if you will, a series of interlocking “passports”, allowing a whole range of activities to take place across the Union, and provide access to the Common Internal Market. And these form the very fabric of financial and commercial life, as various local laws have been consolidated into EU wide directives..

The Chequer’s document, it cannot be described as an agreement, since after it was floated several members of the cabinet resigned, provided the first sign of recognition by a British government of how important this network of longstanding agreements and passports are to industry and commerce. The document, for the first time, recognizes that any Brexit deal will have to recognize the importance of a common rule book, previously ignored in the negotiations.

The aim of the Chequers document is for business to:

“develop a broad and deep economic relationships with the EU that maximizes future prosperity in line with the modern Industrial strategy and minimizes disruption to trade between the UK and the EU” (Chequers p6)

This raises the immediate objection that Brexit has never been about the interests of business, which is almost 100% against the entire idea. The problems with the EU being entirely of a political nature and related to the internal make up of the Tory party.

Following the Brexit referendum, the government interpreted the narrow majority to leave as requiring the country to abolish the free movement of labour, exit from the common market, and reject the role and rule of the European Court of Justice. All of these “red lines” run directly counter to the main goals of the Chequers document as expressed above. Moreover these “red lines” make it almost impossible to participate in the various passports needed for frictionless trade in services.

The Chequers document proposes an Economic Partnership based around a common rule book and a free trade area between the EU and the UK including trade in agricultural goods. This would be built up around a Facilitated Customs Arrangement so that there would be no tariffs on any goods flowing between the EU and the UK[5]. Yet, the entire document follows international practice in excluding any special arrangements for trade in services, and in particular excluding any arrangements around “passporting”. Passporting refers to arrangements where, through the mutual recognition of standards practices and professional qualifications, a single supplier can supply a service product to the entire single European market without any further institutional barriers, insofar as the service conforms with EU definitions and specifications.

The ambitious goal about an Economic partnership stated in the document has very limited political support within the British government itself, and enjoys even less support within the Tory party. Even the coalition partner, the DUP, has expressed hostility to the document and related proposals around the backstop agreement. The backstop agreement is a condition made by the EU and the Irish government in order to prevent the imposition of a hard border between northern and southern Ireland. And for this to work, it is argued that northern Ireland has to become part of the EU for customs and single market purposes. This would go a long way towards maintaining the conditions set out in the Good Friday Agreement that ushered in a period of peace and prosperity in Northern Ireland and ended the period known as the “Troubles”. The DUP is concerned that this would effectively introduce some kind of an administrative border between Northern Ireland and the rest of Britain, running down the middle of the Irish Sea, something they oppose.

Logically such a backstop agreement for one part of the UK ought to extend to the rest of the country too. Politically though this would, it is claimed, deny the “will of the people”, ie the 2016 Brexit referendum result, and be “Brexit in name only”. A potential impasse over the backstop proposition suggests that political difficulties within Ireland could fatally upset constitutional and political plans in Britain, not for the first time.

The subsequent contortions amongst government policy makers to square the impossible circle, and try to squeeze the Chequers document into ever more confining limits, simply to appease Brexiteers, has reduced the chances of it gaining support from the House of Commons as a whole, who now have a duty to exercise a “meaningful vote” on the government’s plans for Brexit. This is even before gaining any reaction to the Chequers document from the EU.

At the recent Salzburg summit (Sept 19/20 2018) , it became clear that EU leaders thought most of the document’s proposals were unworkable, and probably unconstitutional within the EU treaty framework. The European Council suggested that the Chequers document should be extensively reworked and resubmitted. Implying that, like the Dodo, the document is now probably politically extinct, although no one can quite precisely date the time at which extinction actually occurred.[6]

The trouble being that with a virtually extinct Chequers document, this means that there are currently no proposals for a transitional agreement between the EU and the UK on the table (at the time of writing), leaving the way open for a hard, disorganized and chaotic Brexit non-deal. [7]

What does the structure of EU service passports tell us about the EU ?

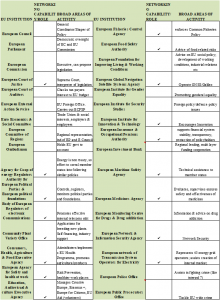

The EU currently supports some 63 agencies that cover many areas. These include institutions such as the European Parliament and European Commission down to EASA, the European Air Safety Agency and EBA, the European Banking Association. A full list is shown in appendix 1. Over half of these agencies have capabilities in organizing and forming networks, and in issuing passports or various forms of permission by which intra EU activities are encouraged, and are carried out. These passport type activities are an essential way in which the EU carries out its business, and they form an important part of the benefits of EU membership, and in being part of the internal common market, and customs union. All of which takes place under a rubric of moves towards closer integration between member states.

Chart 1 analyses the openness of these institutions to 3rd party states. By which is meant whether 3rd party states can join these institutions and participate in their activities.

Chart 1

| Admission of 3rd party non EU members | Number of cases |

| Yes | 3 |

| No | 40 |

| Yes – EEA | 20 |

Chart 1 shows that of the 63 agencies, around 2/3rds are not open to non members. Only 3 are listed as having 3rd party participation. 20 agencies have participation from members of the EEA, who are thus able to enjoy many of the benefits of internal passporting arrangements. EEA members are expected to contribute to the agency budgets for this privilege.

Chart 2

| EU POLITICAL ANALYSIS OF INSTITUTIONS/AGENCIES | |||||

| AGENCY FUNCTIONAL ROLE | # | Yes | Yes-EEA | No | |

| Political Coordination | 8 | 1 | 0 | 7 | |

| Legal/Security | 8 | 0 | 2 | 6 | |

| Regulation | 15 | 1 | 5 | 9 | |

| Labour Rights | 6 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| Education | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Technology | 9 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |

| Security | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Health | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| Agriculture | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Economics | 5 | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

| Energy | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Transport regulation | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| administration | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

Chart 2 analyzed the functional roles played by these agencies, and this reveals that most areas of EU agency activity are effectively off limits to 3rd party countries. There is one case where 3rd party states are involved in political coordination, one in regulation, and one in technology. The chart clearly shows that the key to becoming a more effective partner with the EU, at an “operating” level is for the UK to join the European Economic Area. And if that is too straight forward and direct, then the only other available option might be to follow the Swiss example, which involves as many as 300 different treaties with the EU.

Where is the Brexit Bonanza ?

One of the most infamous claims made during the Brexit campaign by the Leave supporters was that when freed from the clutches of the EU, vast financial resources would be released, to be spent on more socially worthwhile activities, such as supporting the NHS. On an annualized basis it was claimed that as much as £18 billion (€21.3 billion) would become available. Such largess could certainly plug any holes in EU spending that reached the EU, leaving us unambiguously better off. With the passage of time, these claims have been discredited and talk of a Brexit bonanza rarely gets a mention.

Our analysis of the loss of service industry passporting (see below) combined with the consequences of the imposition of tariffs, and other uncertainties for investment and consumption following a Hard WTO Brexit all point to significant down turns in economic activity, and to rising administrative and other costs for government and society.

There is not going to be a Brexit bonanza following a Hard Brexit in the short run. The probability of there being one in the longer term is low to non existent. And this matters because it means the government has virtually no fiscal room for manoeuvre to compensate businesses for losses that will emerge from Brexit, and from the loss of passporting rights.

The OBR[8] published an estimate that current liabilities from the UK to the EU under existing treaty obligations and other mandates are in the region of €41.4 billion, and stretch out to 2064.[9] The peak years for repaying these liabilities will be in 2019 and 2020, when annual payments in the region of €9.5 billion will have to be made. Against that the UK will arguably save on its net annual contributions to the EU. The UK is the second largest net payer to the EU, and after allowing for the negotiated budget rebates, the UK is paying a net €4.24 billion a year into the EU. This, it could be argued, will be “saved” in the event of a Brexit.

However, the government, realizing there will be some real losses arising from leaving various EU programmes, is also committed to compensating the losers. In particular this means compensating those recipients of agricultural support, R&D support and regional cohesion funds.

Chart 3 below shows that current receipts from the EU amount to £ 4.9 billion (€5.75 billion), or rather more than the expected savings of €4.2 billion mentioned above. At the time of writing, there is no agreement within the UK government as to how these funds should be distributed. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (the federal areas) contest the view that these funds should be administered by Westminster, suggesting they belong to the devolved powers of the regional governments.

Chart 3

| Current EU Expenditure Programmes UK receipts | € mill | |

| Technology | 1,448.7 | |

| Cohesion | 607.2 | |

| Agriculture | 3,680.2 | |

| Environment | 22.6 | |

| Total | 5,758.7 | |

| Total GBP mill | 4,921.98 |

The main area where the UK is likely to save money is from membership contributions. After netting out rebates, the amounts involved are shown in chart 4 below, totalling £13.4 billion.

Chart 4: UK membership “fees” to the EU.2017.- a potential saving to HMT

| Sources of Contributions from UK to EU Budget | Amount in Euros mill |

| VAT | 3,199 |

| GNI resources | 12,367 |

| Lump sum reductions | 166 |

| Total Euros | 15,732 |

| Total GBP @ 1.17 | 13,446 |

Source: EU budget statistics and author’s calculations

Is this the long hoped for Brexit bonanza ? Again, bearing in mind the continuing obligations from the UK to the EU as part of any softer Brexit,(€9 billion in 2019 see above) the net amounts “regained” from Brexit are likely to be initially in the region € 6 billion pa in the short term. A useful amount, but far smaller than the amounts originally claimed by Brexiteers at the time of the referendum[10].

Even this “savings” figure is in some doubt, since it assumes that all other aspects of EU spending are somehow useless and irrelevant. On closer examination a case can be made that some of the functions will be repatriated, and spending in other areas by the UK government will have to rise to take on new responsibilities that didn’t exist at that level while in the EU.

Chart 5 provides an overview of some of the areas where additional government spending will be required post Brexit.

Chart 5: Potential Increased Spending by UK government departments post Brexit

| Government Dept | Type of additional Activity |

| Home Office | Visas; tighter immigration controls. Strengthened borders |

| HMRC | Rules of origin for international trade (all trade in goods) |

| Dept of Education/ Home Office | Recognition of academic and professional qualifications And standards |

| Dept of Transport | Enhanced CAA dealing with flight agreements |

| HMRC | Administration of Duty Free schemes on EU/UK visits |

| Information Commissioners Office | Compliance with EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) |

| HMRC/Home Office/Dept of International Trade | Freight forwarding; secure depots and warehouses for customs facilitation scheme |

| Dept of Health | NHS recruitment/Labour quotas/Immigration |

| DEFRA | Environment, food quality standards. Compliance with EU regulations if in EEA type situation; fisheries |

| Home Office/MoD | Security, law & order, borders |

| DWP | EU related pensions issues |

| BEIS | Innovation policy/state support for industry/ Qualifications/professional standards |

| Comp & Markets Authority | UK competition policy, outside of EU |

| Ministry of Justice | Dealing with legal issues following Brexit. Constitutional issues re UK “federation”. |

Faced with a reduction in economic activity, and a need to spent more on government services to “manage” the Brexit process suggests continuing pressure on government spending. The government’s longer term stated goal is to reduce the deficit and borrowing requirement (from around £80 billion a year), while at the same time proclaiming an “end to austerity”, marked by a potential £35 billion increase in spending ! Is this the fiscal Brexit bonanza Brexiteers are waiting for ?

It seems very unlikely to be so. Declines in service output alone are forecast to reduce national output by over 5% (see below for more details). This will reduce the amount of tax revenue raised, particularly from the financial services sector. Chart 6 below shows that the financial services sector contributes around £60 billion in tax revenue pa. This could fall by as much as 1/3rd (£20 billion) following the loss of passporting rights. This, combined with a planned additional spending of £35 billion does not appear feasible under conditions expected post Brexit.

All of this suggests that there is little to no room for fiscal expansion by the government to compensate those sectors facing Brexit induced losses. There is no Brexit Bonanza. The choices facing the government would appear to be to raise either taxes, or borrowing, or both. Thereby cutting yet more of the government’s own red lines.

The Importance of Services for the UK Economy.

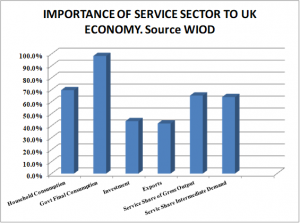

It is an oddity that while much attention is given to the manufacturing sector in terms of UK policy prescriptions, much less attention is paid to the service sector. Yet, the service sector is by far and away the most important part of the British economy. Just how important is shown below in chart 7.

It constitutes nearly 70% of final household consumption, just over 40% of investment, and a similar proportion to national exports. If there is one area where it would inadvisable for a government to willingly intervene to its detriment, then it would be in the service sector.

Chart 7

Yet, given the state of the recent negotiations with the EU, as well as the internecine warfare within the governing party and within the government itself, this is precisely what is on offer at the moment.

An associated difficulty is that the breadth and complexity of the service sector makes it hard to analyse collectively. The lack of observable tariffs on foreign trade in services is another element that makes them almost invisible to policy makers. With the growing probability of a Hard Brexit it is time to look more closely at the sector, and in particular to concentrate attention on:

- The transport sector – air and land

- Financial services, and in particular banking and insurance.

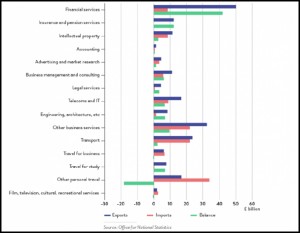

Chart 8 provides an overview of the performance of the services sector in foreign trade. All the service sectors bar “other personal travel”, business travel, and film & TV earn a surplus on the current account. Financial services earn a particularly large surplus, and about one third of this is due to business with the EU. Financial services is striking for the large foreign trade surplus earned.

Chart 8: Foreign Trade Performance of UK Service Industries

Source: NIESR Blair Institute Report

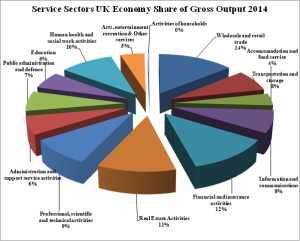

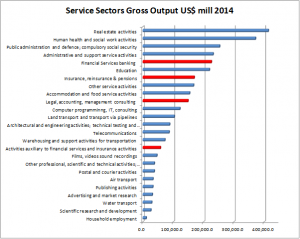

Chart 9 below compares the size of the service sector in terms of gross output. Financial services has the highest share of gross output of all the service industries.

Chart 9

One of the main reasons for the foreign trade success of many sectors of the British service industry lies in the nature of various passporting arrangements established by EU member states. These proceed from the mutual recognition of various rules valid across the EU. So long as these rules are adhered to (“the rule book” as it is referred to in the Chequers Document), then companies located in any one member state can generally open up businesses across the Union, and can also export products from one country to another without let or hindrance. This has been of particular benefit to smaller companies, for whom the costs of establishing foreign businesses are proportionately higher than for larger competitors. A Hard Brexit puts this entire system at risk.

One example taken from the air transport industry should make clearer what is involved. The US does not allow third party foreign airlines to pick up or set down passengers and freight at any US airport en route to its final US destination. Foreign airlines are engaged on point to point flights, there and back. This also undermines the competitiveness of foreign airlines operating with the US, since they have no access to profitable cabotage possibilities (see below for more details). In the EU, airlines can establish routes from any point to any point within the EU. This may involve round trip flights from say, the UK, to Poland, to Italy, to Spain and then back to the UK. As a 3rd party state following a Hard Brexit, it is entirely possible that this type of air traffic will no longer be possible for UK based airlines (see below for further clarification).

The lack of passporting rights may be regarded by outsiders as a form of non tariff barrier. Seen from an EU member states perspective, passporting rights are one of the benefits that membership of the Union brings, and is part of the European integration process. This point has been fundamentally misunderstood by Brexiteers.

A second reason for the importance of services in the UK is that a great deal of business is transacted in English across the EU. Although it is but one of the main official languages, de facto more meetings, publications, contracts and other important documents are drawn up in English than any other EU language – particularly where the contracts involve more than one member state. This gives English speaking countries something of an advantage.

Britain’s advantage is emphasized by its strength as a financial market hub, something that is legacy of earlier imperial times, as well as from legal changes in the US that drove some of their financial business overseas, as well as a favourable location in terms of time zones.

All of these factors, when combined, have given the UK a comparative advantage in the provision of various financial services. Financial Services business is divided between domestic, EU based, and Rest of the World (ROW) based. The size of the EU and ROW business is similar, accounting for about 25 to 30% each, depending on the sector. This is now under threat following a Hard Brexit.

The following sections will look at the transport and financial services industries in more detail, to form a more accurate view of the likely impact of a Hard Brexit.

Air Transport

Air Transport has benefited from the EU far more than is commonly realized. It was the EU that brokered the Open Skies Agreement that greatly enhanced the role of cheap budget airlines, and helped to revolutionize the cost and frequency of intra EU flights. This in turn allowed customers to benefit from the geographical diversity of Europe without being hampered by the many layers of bureaucracy and high costs that earlier made frequent intra EU air travel the preserve of the rich.

This was achieved through the creation and availability of the “nine freedoms” available to intra EU air traffic operators, as a matter of right for EU airlines. 3rd party airlines are still bound by more restrictive conditions meaning that they do not gain the benefits of all 9 freedoms. This in turn affects the profitability of 3rd party airlines flying to and from the EU, since they have less flexibility than domestic EU flights.

Chart10. Summary of 9 freedoms.

| Freedom Number | Freedom Description | Comments |

| 1 | Overlying rights | Basic requirement |

| 2 | Refueling rights. Aircraft can land, refuel en route to Final destination | |

| 3 | Point to point scheduled flights from one country to another | Enables flying from country A to Country B. One Way |

| 4 | Point to point Scheduled flights from One country to another. Return flight | Enables return flight to home country |

| 5 | Scheduled flights can stop at a 3rd country en route home, bring passengers home. Flight has to connect with home state | Valid for inbound flights to home country. Allows greater flexibility in the use of aircraft. Raise load factors on return flights |

| 6 | Scheduled flights can stop at a 3rd country and can take passengers to main destination country. Flight has to connect to home state | Valid for inbound flights to home country. Allows greater flexibility on out-bound flights |

| 7 | Scheduled flights can stop at 3rd country and take passengers to main destination | Flight does not necessarily have to connect to home country |

| 8 | Outbound flights from home can pick up passengers within the final destination country at more than one airport | Means that an international carrier can function as a domestic airline in the destination country, if flight connected with home territory |

| 9 | A carrier can pick up passengers in different parts of main destination country, without the flight having originated in home country | International carrier can function as a domestic carrier in destination country, even if the flight does not involve the home country |

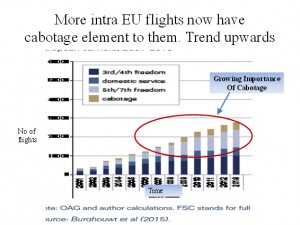

The various freedoms are quite complex. At the same time they open up many more possibilities for airlines who are engaging in what is otherwise known as cabotage. The extent of this can be seen in chart 11 below. This shows the number of intra EU flights that now contain a cabotage element to them is about the same as the number of more limited point to point flights.

This has important financial and operating impacts on airlines. By replacing earlier bilateral agreements that broadly favoured national flag carrying airlines, the EU arrangements have dramatically increased competition within the EU, and in the EU neighbourhood.

Chart 11

Given the geographical proximity of EU destinations and the nature of air travel, a large majority of air traffic movements are between EU member states, including between EU and EEA members. The bulk of long haul international flights in the UK are routed through London Heathrow, with other long haul (non-EU) flights being routed via Gatwick, Manchester, Birmingham, Glasgow/Edinburgh. The remaining flights from the many UK based airports are almost entirely involved in air traffic with the EU.

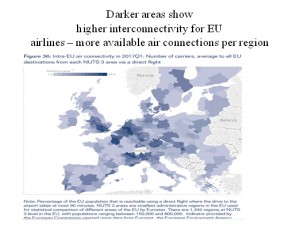

The importance of intra EU flights and flight connectivity is shown below in chart 12. The darker the area (defined as a NUTS 3 region taken from Eurostat) show some interesting patterns The areas of greatest connectivity across the current EU are South East England, Paris, Benelux, North and central Germany, Denmark (Copenhagen), and Sweden (Stockholm). The other areas of high inter-connectivity tend to be in tourist destinations around the Mediterranean, as well as skiing resorts around Switzerland. Interconnectivity of flights falls away as one moves East across the EU, reflecting continuing differences between Eastern and Western Europe.

Chart 12

Chart 13 below provides some closer observations of the proportions of domestic and foreign traffic for the UKs two major airlines, Easyjet – arguably a great beneficiary of the EU Open Skies policy, and British Airways, more likely to have been one of the losers.

Chart 13 Estimates of EU passengers by airline and main airport

| Airline | All Schedule Passengers mill | International Passengers mill | International % Total | EU % of International | Estimated EU passengers | EU % Total |

| Easyjet | 64.1 | 56.1 | 87.5 | 0.95 | 53,4 | 83.5 |

| British Airways | 42 | 36.8 | 87.6 | 0.75 | 27.6 | 65.7 |

| London Heathrow | 75.7 | 71 | 93.8 |

Source: DfT Table BB0213 (AvIO 302) 2016 & authors calculations

In our view EU related air traffic probably represents around 70 to 80% of all passengers, and a similar share of air freight traffic. This high dependence means that the air transport sector is very vulnerable to any potential interruptions in air travel arrangements following a Hard, chaotic Brexit.

Current EU/UK arrangements for Air Traffic

Prior to the EU’s Open Skies arrangements, Air traffic was subject to a host of bi-lateral agreements between sovereign states. Given the small size of most EU member states this was highly inefficient and restrictive. It meant that frequently there were only two flag carriers on intra EU routes, one from each country, enjoying essentially a monopolistic/oligopolistic control over flight frequencies and prices. Prices were extremely high and air travel was a luxury. Airlines were largely restricted to freedoms 1 to 4, which supported the limited point-to-point services. These agreements were known as Air Service Agreements, and there were many of them.

This national solution was replaced by a horizontal agreement between EU member states and EU. This set up the European Common Aviation Area (ECAA), which opened up the internal market – in just the way that many UK Conservatives were keen on. All EU member state licensed airlines were eligible for all nine freedoms. This meant that could open up routes from anywhere to anywhere within the EU with little further regulation – assuming they were compliant with the EU regulations (see below).

The EU approach to air transport consists of 3 pillars. And it is notable that under this arrangement any 3rd party countries have to deal with the EU via the European Council and the European Air Safety Agency (EASA). Earlier bilateral arrangements are now a thing of the past, with one or two exceptions.

Pillar 1 consists of the consolidation of national bilateral treaties into one, horizontal, EU wide agreement. This was done to ensure that all the former national ASAs conformed to the EU rules and regulations. The advantage for EU member state airlines was their participation in all 9 freedoms.

Pillar 2 is a comprehensive agreement with 3rd party states that are geographically close to the EU, in the neighbourhood so to speak. They could then join the ECAA. This group of countries covers the EU, Albania, Bosnia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Kosovo, and Norway and Iceland from the EEA. Pillar 2 extends EU safety standards to all participants, replacing earlier bilateral treaties. Pillar 2 acquisitions can only be negotiated via the European Council.

Pillar 3 is a similar arrangement for countries not in the EU neighbourhood. Agreements with the US and Canada fall into this category, and involve the mutual recognition of safety and other standards.

This structure sits ill with ideas of a Hard Brexit. As a 3rd party state the UK will have to negotiate a new agreement with the EU, not with individual member states. And while the UK’s existing technical and safety standards are aligned with those of the EU, there may be commercial issues on whether the UK would automatically achieve all 9 freedoms on accession to the ECAA.[11]

With respect to a Hard Brexit, these arrangements point clearly to the acute necessity for the UK reaching an agreement on air travel with the EU via the European Council and EASA. If there were hopes amongst Brexiteers that a bit of “cherry picking” and resetting to the old bilateral ASAs would rapidly lead to a resumption of air traffic connections post Hard Brexit, they will be disappointed.

Let us end this section on air transport with the following observation taken from the recent ITC report (“The Strategic Challenges Facing UK Aviation”):

“…the EASA is responsible for the authorization and oversight of relevant activities by firms from 3rd countries that want to participate in the EU market. The exceptions to this are the ones where there are bilateral mutual recognition of standards agreements.” p. 74.

This currently includes the US and Canada. EFTA is represented on EASA and observer status for 3rd countries is possible. Thus it will be possible for the UK to join EASA and the ECAA at some point. As a 3rd party country though UK airlines may not be extended the full 9 freedoms they previously enjoyed. If not, then the airlines, while remaining in the UK, would suffer a medium term impairment of their business. The entire process would be greatly simplified were the UK joined EFTA/EEA beforehand.

Land Transport

The Land Transportation industry accounts for between 4 and 5% of employment and 4 and 6% of national value added, making this an important industry. It is also key for the delivery of just in time freight consignments, and in supplying a very large range of goods to industry and consumers. The smooth functioning of much of the economy depends crucially on receiving prompt delivery of goods required at the time when they are needed.[12]

For the UK consumers and industry are entirely used to receiving prompt deliveries, interrupted perhaps by traffic congestion or bad weather. At the current pre Brexit time, it is rare for there to be significant hold ups at Customs. A hard Brexit will change all of this dramatically.

All land transport, via ferries and the Channel Tunnel is necessarily with the EU, or with the EEA (Norway). Hence any changes in the rules affecting customs clearance will have an immediate impact on the flow of freight traffic and on the time spent waiting for customs clearance.

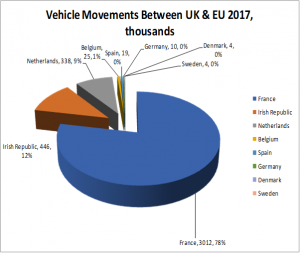

Chart 14 analyzes vehicle movements between the EU and the UK by destination country. Nearly 80% of vehicle movements are between the UK and France. This is the shortest and cheapest passage, and is also the route covered by the Channel Tunnel. The second most popular destination is Ireland, which helps to explain why the backstop is so important to the Irish economy. The third most important route is to Rotterdam in the Netherlands. This is a transhipment point for goods going further afield into the EU as well as goods being exported to inter-continental destinations.

Chart 14

Source: Department for Transport

Britain, as a member of the EU is also a member of the Customs Union, meaning that there are no tariffs or controls on intra EU freight.[13] Customs dues are collected on inbound cargoes coming into the UK from the rest of the world. The UK government collects import duties on behalf of the EU. This affects land transportation rarely at the moment, with the result that the customs infrastructure at most British ports is simply not able to cope with an abrupt change to a post Hard Brexit introduction of WTO based tariffs.

The Chequers document mentions that post Brexit the UK might get around to joining something called the Lugano Convention, that most other EU states signed up to back in 1973, and this is smuggled in as if this is a casual improvement, a remedy for a careless slip of the pen all those many decades ago.

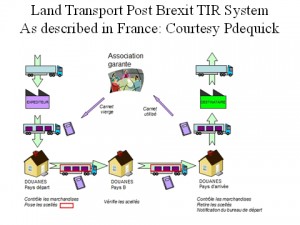

It pays to read between the lines when perusing the Chequers document. The Lugano Convention is associated with the Transports Internationaux Routiers, or TIR. These blue and white signs were a familiar sight on the Continent, although less often seen here. Charts 15 and 16 summarize the situation pre, and possibly post Brexit

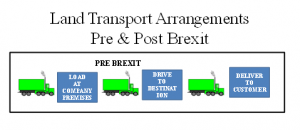

Chart 15

The current arrangements are a model of simplicity. A company gets an order for its goods. It either hires, or uses one of its own trucks. The truck is filled with goods, probably put in a container. The truck is driven to the port, boards the ferry/joins the channel shuttle. Waiting times are minimal. The truck disembarks, drives to its destination, and delivers its goods. If it wanted to, it could then pick up another cargo for return trip, similarly un-bureaucratic. The formal paperwork, other than that needed for a normal transactions between business partners, is minimal. The EU kindly requests that if the cargo has a value of more than a certain amount (a high threshold has been set), could someone please send a form to Brussels, letting them know when, where and how much.

How does this compare with the TIR scheme, being launched on an unsuspecting British freight industry and general public? Chart 16, taken from a French publication provides a succinct summary. First of all an exporter has to buy an export TIR carnet. This is normally a complex document. It has to specify from where the goods are to be despatched, the route to be taken, the time to be taken, and the point of destination, where the goods are to be unloaded. In the past drivers had to take with them sufficient funds to pay for import duties, should the truck get delayed on route, have an accident or other problem. The route was carefully specified, and the vehicle had to report in at all border crossings en route. Finally, the vehicle had to report to its destination customs office/warehouse. The goods might then have to be unloaded there, while the customer came to pick them with their own vehicle.

While the TIR system represented a big step forward compared to earlier times, most people would agree that this is not exactly going to produce quicker journey times, and less bureaucracy. It will in any case add to the costs of exporting goods, and hence to the working capital requirements of the exporter – something that never gets mentioned by government or the Brexiteer lobby.

Chart 16

The current situation is outlined in chart 17 based on World Bank information. According to the World Bank, the UK’s time needed to prepare export documentation is, at 24 hours the worst in the group – even longer than needed in Turkey. It also has the second highest cost of preparing the export documentation, after Turkey. Other processing time for exports are not particularly good. The situation is much better for imports into the UK, which can proceed with virtually no interruptions, additional costs or other delays.

Chart 17: Times & Costs Involved in Exporting and Importing: Selected Countries. Source World Bank

| Economy | United Kingdom | Bulgaria | Switzerland | Norway | Turkey | OECD High Income |

| Time to export: Border compliance (hours) | 24 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 12.7 |

| Cost to export: Border compliance (USD) | 280 | 55 | 201 | 125 | 376 | 149.9 |

| Time to export: Documentary compliance (hours) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2.4 |

| Cost to export: Documentary compliance (USD) | 25 | 52 | 75 | 0 | 87 | 35.4 |

| Time to import: Border compliance (hours) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 41 | 8.7 |

| Cost to import: Border compliance (USD) | 0 | 0 | 201 | 125 | 655 | 111.6 |

| Time to import: Documentary compliance (hours) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 3.5 |

| Cost to import: Documentary compliance (USD) | 0 | 0 | 75 | 0 | 142 | 25.6 |

Chart 17 provides a clue to some of the difficulties lying ahead when the situation regarding Turkey is considered. It costs a lot – US$ 655 at the border, followed by another US$ 142 inland to complete the customs formalities. It also takes 41 hours waiting at the border to gain permission to finish the journey within Turkey. That is nearly 2 days of waiting time !!

Turkey is part of the Customs Union with the EU, meaning that there are no import duties to pay on goods going across the border[14]. Under a Hard Brexit scenario, Britain will not be part of the Customs Union, suggesting a whole area of delays not applicable to Turkey.

In a recent article in the FT[15], the situation at the main border crossing into the EU at the Kapikule border crossing were described. Waiting times of between 17 and 30 hours are regularly reported there.For trucks leaving Turkey they are expected to have the following documents. An export declaration; a TIR carnet; invoices for the cargo; insurance certificates; transport permits for each country the truck transits in order to get to its final destination. Trucks are also subject to random X ray checks on entering Bulgaria.

Turkey does not sign up to free movement of people, meaning that truck drivers have to get short stay visas for the Schengen area and any other non Schengen EU countries they might pass though, and this too takes time.

Truck transit visas are also highly problematic, and are issued by the member states. A truck requires a transit visa for each country it goes through, and Schengen does not count as a single area. The process by which transit permits are granted is opaque, and varies from country to country. There is no guarantee that the number of permits issued corresponds to the actual demand for permits.

These are the sort of conditions currently faced by land transport between Turkey and the EU, where to recall, Turkey is already part of a customs union with the EU. In a post Hard Brexit UK it highly likely that border crossing times will greatly lengthen, and border crossing delays will become endemic.

Taking some recent figures from Turkey’s border crossing at Kapikule (with Bulgaria), and comparing them with border crossing vehicle movements at Dover is eye opening. Dover processes some 9.25 trucks a minute, compared with between 2.5 and 3.3 vehicles per minute in Turkey. There are traffic jams of between 17 and 30 kilometres on both sides of the border in Turkey/Bulgaria. Translated into the Dover situation, this would lead to traffic jams of between 5 and 10 kilometres on the M20, without considering the situation at the Channel Tunnel. The delays will quite probably take on Turkish proportions. And all of this for the sake of a Hard Brexit ?

The analysis presented here follows directly from the casual mention of introducing the TIR agreement and processes into the UK, and to try and present them as a modernizing, step forward for British road hauliers. Nothing could be further from the truth. This is a step backwards to the mid 20th century, and to conditions many of us thought we’d never see again. Many of these points have a direct bearing on the negotiations around the backstop needed by the Republic of Ireland with the 6 counties in the North to ensure a “frictionless” border. As this analysis shows, the default position for border crossings under a Hard Brexit are anything but “frictionless”.

Financial Services and Passports

Financial Services are considered to be the jewel in the crown of the British economy. It is an area in which the country excels, and London is generally considered either the first or second best global financial centre, putting it and New York into a different league from the others. And of the two, New York has a much stronger internal US focus, whereas London is premier for international transactions, and as acting as a bridge between the US and the EU.

Chart 18 shows the gross output for all service sectors in the UK economy. The financial services are marked by the red bars. The three largest financial sectors are ranked 5th, 7th and 10th by size of gross output. If all are counted together, then this becomes the largest bloc of services, exceeding all the others. So once again, negative developments here will have widespread consequences for the rest of the economy.

Chart 18

Source: GIOD/authors calculations

Definitions of financial services vary. Chart 19 shows a view presented by Eurogroup.Total revenues for financial services in the “base year” came to £197 billion, and the sector employed over 1 million people. In revenue terms retail banking was the largest, followed by corporate and investment banking (CIB) and insurance at over £40 billion a piece. This was followed by asset management and a broader IT and transactions support services called the “eco system”.

Chart 19 Base Year (2016) Estimates of Size of financial services

| Financial Sector Sub Sector | Revenues GBP bn | Employment |

| Total | 197 | 1050 |

| Corporate Investment Banking | 44 | 110 |

| Retail Banking | 63 | 460 |

| Asset Management | 27 | 68 |

| Insurance | 41 | 320 |

| Stock Exchange | 4 | 11 |

| IT, “eco system” | 18 | 85 |

The two largest employers are retail banking and insurance, and a large proportion of their business is domestic. A recent House of Lords report stated that financial services collectively accounted for 7% of UK GDP. 2/3rds of the sectors employees were located outside of London. Financial services generate high volumes of tax, and are successful exporters. Financial services paid £60 billion of taxes, with domestic banks paying £31 billion, and foreign banks paying £15 billion. Additionally there are a wide range of ancillary services dependent to a degree on the financial sectors mentioned above. Chief among them are management consultancy (483 k employees), legal services (314 k employees) and accountancy (391 k employees).

The successful development of the UK’s financial sector was encouraged by the creation of the EU, and through the establishment of passports. As has been seen in other sectors, passports are a device where, subject to the mutual recognition of standards and rules, individual companies and operators are able to do business across the whole of the internal market. In the case of financial services, these passports have taken a number of special forms.

Chart 20 UK Financial Service Passports

| Passport Category | Outbound from UK | Inbound to UK | Ratio out/inbound | Predominant flows |

| AIFMD ( inv funds) | 212 | 45 | 4.7 | Outbound |

| IMD Insurance Mediation | 2758 | 5727 | 0.48 | Inbound |

| MIFID | 2250 | 988 | 2.27 | Outbound |

| MCD Mortgage Credit Directive | 12 | 0 | Outbound | |

| PSD Payment Service Directive | 284 | 115 | 247 | Outbound |

| UCITS | 32 | 94 | 0.34 | Inbound |

| CRDIV | 102 | 552 | 0.18 | Inbound |

| Solvency II | 220 | 66 | 0.3 | Inbound |

Source: House of Lords Table 2 p 12 & authors calculations

Chart 20 shows that passports are issued around specific pieces of legislation. This legislation in turn provides a basis for operating within the EU’s common market. This legislation provides the bedrock for cooperation and the mutual acceptance of standards. It also provides access to EU retail finance markets, such as with UCITS for fund management. A UCITS approved fund can be sold to retail customers across the EU. And UCITS is something open to EU member states only.

The main fund management related passports are with the Alternative Investment Fund Management Directive, dealing with alternative stock market quoted assets and funds. And UCITS The main passports for insurance are Solvency II and the IMD Insurance Mediation. CRDIV, PSD and MCD are of importance for banking; MIFID deals with trading rules and treatment of customers, so is relevant to stock exchange participants and other trading activities in other financial markets. Without access to these passports, UK financial institutions will not be able to operate freely across the EU’s internal market. Equally, EU companies may find they too will not automatically be able to operate in London, without gaining permission from British regulators.

Chart 20 shows clearly that the issue of passports works in both directions. There are four categories where there is more inbound traffic than outbound – meaning that EU based institutions are interested in operating in London. There are also four areas where there is more outbound need for passports, indicating UK firms aiming to gain access to the wider EU market. These include alternative investment management funds, MIFID for market trading, MCD mortgage directive and PSD for payments systems into the EU.

The legislative underpinning of passports

The passports refer to specific pieces of legislation, which in the main apply to different part of the financial services sector. The main ones are listed below:

- Capital Requirements Directive IV (2013), incorporating various risk measures and the Basel III arrangements.All deposit takers, ie banks, have to sign up to this

- Solvency II.This affects the insurance industry and its capital requirements to conduct various types of insurance business (contracts). Solvency II requires that 3rd party countries will need to establish a fully fledged branch somewhere in the EEA in order to continue to do business

- MIFID (2007), MIFID 2, MIFIRC (Markets in Financial Instruments Regulation) June 2018. MIFID compliance is needed for a whole range of financial trading operations. These include trading in securities, and funds, derivatives, trade execution, investment advice, underwriting, IPOS and traditional financial asset trading. FIFIR allows 3rd country access to these internal EU markets.

- UCITS (1985 and 2014). This is needed in order to market and sell retail fund management products across the EU single market. There is currently no 3rd party access. A fund management company would have to have a domiciled subsidiary within the EU in order to carry out business. This would not prevent the actual fund management activity staying in London.

- AIFMD (Alternative Investment Fund Management Directive. This sets out common rules for alternative investment funds. This is an EEA wide passport.

The regulatory situation evolves. There are important principles around the “equivalence” of 3rd arty regulations. Where these are considered adequate, then mutual recognition can be given for access to the internal EU market. [16]

How large is the dependency on the EU?

This is quite a difficult question to answer. The answer can depend on whether one is referring to the location of institutions investing or trading, or the location of their clients. These are not necessarily the same thing.

Chart 21

| Col totals % Shares | Total | Banking | Asset Management | Insurance & Reinsurance | Market infrastructure & other | |

| Domestic business earned from UK clients | 46.8% | 58.7% | 69.1% | |||

| International and wholesale business related to the EU | 22.8% | 21.7% | 25.0% | 9.9% | 42.9% | |

| International and wholesale business Rest of World | 30.4% | 19.6% | 75.0% | 21.0% | 57.1% |

Source: Oliver Wyman (2016).

Chart 21 uses materials from Oliver Wyman (2016) who produced a wide ranging and seminal report shortly after the referendum. The chart provides a summary view of the split in business between domestic, EU and Rest of World activities by the different parts of the financial services sector.

The overall figures suggest that London’s business with the rest of the world is larger than with the EU across all categories[17]. The differences are relatively slight in banking. It is also striking that in total less than half business volumes in the financial sectors are in the domestic market – although the shares in banking and insurance are both much more slanted towards the domestic market.

The values shown for the share of financial sector sales to the EU provide one way of considering the “value at risk” in the case of a Hard, chaotic Brexit. If, in an extreme case, all EU business became impossible, this would represent between 20 and 40% of each sub-sectors sales. A worryingly large proportion.

There are a number of controversial sub-plots to all of this too. One of the bones of contention between the Eurozone and London has been the location of Euroclear. Eurozone regulators and the ECB have favoured moving Euroclear out of London to a base within the Eurozone itself, where it can be better regulated. The difficulty being that the London exchange/subsidiary of Euroclear is by far and away the largest part of the operation.

The old arrangement was for Euroclear to be based in London and to be tax resident in Switzerland. This has now changed, with Euroclear now being legally run from Belgium (Brussels). Much of the business formerly integrated in London will now be distributed across Brussels, London and Dublin

According to the Deutsche Bank, a significant shift in Euroclear activities to the European mainland could require an additional £14 billion of funding by British based firms. If the contractual terms also changed, so that netting out of the positions would no longer be possible, then this could give rise to a need for a further £15 billion, implying a call for a total of £29 billion to compensate for institutional changes brought about by Brexit.[18]

Branches and Subsidiaries

Responses to a Hard Brexit are most frequently argued in terms of impact on the nation (the UK), and the EU (a federal union). What is sometimes overlooked is that there are differences between Brexit’s impact on the UK, and on British firms.

British firms with extensive business interests in the EU have to think carefully about how to protect that business, and what the likely costs will be. The extreme case is that various restrictions are introduced in the UK, for instance on the mobility of labour, that compromise the viability of the business in the UK. This could force UK companies, as well as foreign based companies to effectively emigrate and re-locate to the other side of the Channel.

A less extreme solution would be for an UK based operation to reorganize its activities such that they can continue, independently of the situation within the UK. Thus British companies can, for some purposes, set up EU based operations that are run entirely from within the EU.

This has the implication that the costs to individual UK firms of a Hard Brexit might differ substantially from the costs borne by the country as a whole. It is possible in many cases for British companies to reorganize their EU operations in such as way as to ensure continued access to these markets. It will not be cost free, but the costs may be smaller than those involve in losing access to the EU market altogether.

In financial services this often comes down to understanding the basis for operating with a branch network – as is mostly done at the moment, and operating through fully, or partially, owned subsidiaries. In banking this also has resonance with supervisory and regulatory authorities such as the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) and the European Supervisory Authority (ESA).

A branch does not have a legal personality of its own. It is simply a place of business outside of its headquarters/registered address. A subsidiary does have its own legal personality, and is therefore subject to both local and EU laws if it is located within the EU. This means that a subsidiary effectively has all the passporting rights previously enjoyed by the British parent company. This also affects aspects such as deposit guarantees, resolution procedures in case of bankruptcy and winding up procedures, and investor compensation.

For UK banks this comes at a price. Each subsidiary requires its own balance sheet, with its own reserves and capital. The levels of capital in turn determine the volumes of business it can conduct, policies that it can write, and loans that it can provide.

The beauty of the existing EU arrangements is that there is mutual recognition of local standards, and financial institutions are free to set up branches across the EU. Post Brexit, there is no longer any mutual recognition of standards. Business by UK banks in the EU and EU banks in the UK will have to operate via subsidiaries.

It is therefore highly significant that the Bank of England stated in 2017 that EU banks could continue to operate in London on the basis of their existing branch network, thus helping to preserve current business volumes in London[19]. This may have longer term implications on competition in the industry across the EU. Unless there is some reciprocity of this offer by the EU, EU based banks will be able to leverage their capital and reserves more effectively in bidding for business in London, than UK based banks will be able to do within the EU/EEA. Although this sounds relatively trivial, it may over time reduce the profitability of EU operations for British banks, possibly to the point where the business is closed or sold to EU based operators.

Chart 22: Announced Relocations from London. Banks & Investment Banks

| Destination City | employees affected | # banks relocating | % of employees being relocated | % of announced relocations | |

| Frankfurt | 2320 | 12 | 41% | 44% | |

| Paris | 2105 | 6 | 37% | 22% | |

| Dublin | 995 | 6 | 17% | 22% | |

| Amsterdam | 250 | 2 | 4% | 7% | |

| Brussels | 20 | 1 | 0% | 4% | |

| Total | 5690 | 27 | 100% | 100% |

Source: Saville Studley & authors calculations.

As has been widely forecast, the uncertainties surrounding the Brexit process are already unleashing forces very different from those envisaged by Brexiteers. Chart 22 summarizes the announced relocations by 27 banks and investment banks as a reaction to Brexit. Currently nearly 5,700 employees are affected, still a relatively small proportion. The most popular re-location destination for banks is Frankfurt, the home of most EU debt issuance already. Paris and Dublin are the next most frequently mentioned.

These are initial figures, and depending on the nature of a Hard Brexit, this relative trickle could easily change into a more substantial exodus at a later stage.

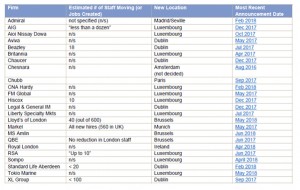

Chart 23 shows the situation for insurance and asset managers. Their preferred relocation destinations are Luxemburg and Dublin. Most of them will consolidate their existing EU business by setting up new fully fledged subsidiaries in order to access EU retail markets.

This does not preclude the continuation of many technical functions in London/the UK. In the absence of an uplift of business with the rest of the world, it suggests that growth in UK based insurance operations is likely to slacken as a result of Brexit. A Hard Brexit would probably accelerate this trend. These announced moves also highlight the deficiencies of political processes that appear to show little or no consideration for the actual practical needs of the financial and other sectors in reacting to the changed circumstances facing them post Brexit. This can only be described as a shocking dereliction of duty by a government towards its citizens.

Chart 23

Summary: Hard Brexit Impacts on Service Sectors

The previous sections summarize some of the more obvious, and in some cases, actual delays, costs and uncertainties likely to be caused by Brexit in general, and by a Hard Brexit in particular. The list of effects is incomplete, and doubtless others will emerge with the passage of time.

There is little doubt that membership of the EEA, or the attainment of a status similar to Switzerland would be preferable from an economic and business point to view to a Hard Brexit. In our view the amount of disruption likely to occur following a Hard Brexit appears highly irresponsible, and constitutes acts for which there is no popular mandate. Whatever one’s opinion about the 2016 referendum, it was never stated that Brexit would result in a poorer and less efficient country, with widespread regional disruption in the shorter term, to be compared with a very uncertain prospect of hitting a trade jackpot in some far away country or countries. And even if such were to occur, the chances of this outweighing the losses experienced as result of losing access to the EU are negligible.

The section highlights the practical importance of passporting in a number of different guises and situations. Passporting, as has been clarified are not some minor exotic “procedure” affecting a small number of services. Passports more generally represent the way in which the EU does business. And it is becoming painfully obvious that the depth and extent of these passports has been completely underestimated in considering the effects of Brexit.

The meso sector impacts of Hard Brexit on Services in the UK economy

To understand the larger economic impact changes in the service sector might have it is useful to apply Input-Output analysis. This is an approach that uses Input-Output tables that show all the key economic relations between the economy as described by a 55×55 matrix. The table shows each industry’s inputs in the columns, and each industry’s output as a row. Each industry requires materials from supplying industries. And each industry delivers a surplus, expressed as final demand (goods that are consumed and don’t re-enter production) This records the extent of supply and demand between the different sectors, and how much of the sector’s output enters into final demand or consumption.

In previous papers on Brexit we have considered global changes in demand based on the views of many other studies. The IO approach enables us to consider both the direct impact of changes in demand, as well as the indirect, or multiplier effect, of how changes in one industry in turn affect the fortunes of another. The IO tables provide a way of tracing through these “ripple” effects. So, it is possible to estimate what the drop in demand for say, food might be, following on from a change in demand for automobiles.

On this occasion, drawing on the information and views shown in the service sector analysis above, we can estimate what the likely impact on the economy might be. Thus, estimated changes in land transport, air transport and financial services will be fed into the model, to understand what the impact of the loss of passporting rights is likely to have on the economy as a whole (all sectors). And it should be noted that this is before introducing any broader changes in final demand across the entire economy as was done in two previous papers, Black 2017a and Black 2017b. The analysis is conducted using an input-output table from the World Input output Database (WIOD).

Input Assumptions.

Drawing on the previous analysis, a scenario was constructed that involved the loss of passporting rights to the EU following a chaotic Hard Brexit. The expected reduction in final demand for a number of service sectors approximately mirrors the EU’s current share of sector turnover, as far as is known. The rest of the economy is left untouched in this scenario, which is rather unlikely in practice.

Chart 24 shows the ex ante assumed reductions in final demand for each affected service sector, and outcome in terms of the achieved output changes needed to maintain the rest of the economy. The assumed reductions in final demand correspond, approximately to either the loss of business with the EU, or a very marked reduction in it. In the previous sections the EU frequently accounted for between 20 and 35% of activity in various services. In Land transportation it accounts for 100% of activity.[20] For the purposes of the exercise, no other ex ante changes in final demand for the other sectors are assumed. This means that what is being observed here are the ripple effects as reductions in final demand for a few sectors spreads throughout the economy. Note, the model assumes that all the changes happen instantaneously, whereas in reality the changes might take place over a longer period of time. Note too that the model is making no assumptions about any exchange rate changes or include any impact of inflation on both domestic and foreign demand.

Chart 25 (below) shows the changes in gross output that occur following the service “slump” scenario. The service sectors are marked with the yellow bars. Red bars denote changes in government activity, and the blue bars refer to the goods sector. This will be affected by tariff considerations, as has been discussed in the earlier papers.

Chart 24: Scenario: Loss of passporting rights and reduced access to EU markets in selected service sectors

| Sector Name | Initial Assumed Final Demand Reduction | Achieved Reduction in gross output | Explanation |

| Land Transport | -45% | -20.4% | Extensive delays on EU frontier. Inadequate capacity at ports |

| Water Transport | -20% | -18.6% | Fewer trucks and passengers to transport |

| Air Transport | -34% | -28% | Loss of freedoms, & cabotage business in EU |

| Financial Services (Banks) | -35% | -22% | Loss of passporting rights. Relocation to EU. EU subsids established |

| Insurance | -22% | -19% | Loss of passporting rights. Shift to Lux and Ireland |

| Auxiliary Financial Services | -24% | -21% | Knock on effects from financial services |

| Real Estate | -23% | -22% | Reduced foreign demand for property |

| Science & Technology | -37% | -25% | Loss of passporting.Loss of EU technology support |

| Post & Telecommunications | -9.6% | Lower activity in financial services. | |

| IT Computers/programming | -4.7% | ||

| Legal Services | -6.7£ | Reduced demand from financial services & EU | |

| Telecommunications | -4.1% | Lower Demand. Loss of EU roaming rights | |

| Government Admin/Support | -4.2% | ||

| Government: Admin/Defence | -0,5% | ||

| Government: Education | -2.34 | Loss of Horizon 2020 support. Erasmus | |

| Government Health | -1.35% | Labour supply restrictions | |

| Overall Impact | -14.9% | -6.4% | Strong overall impact as a result of losses in narrow range of services following loss of passporting rights |

Chart 25: Changes in Sector Gross Output across the whole economy following Service Sector Scenario

Source: Digit IO model

Chart 25 also shows that there will be some quite pronounced impacts of a service slump scenario on sectors such as chemicals, oil, printing and paper, as well as on electricity/gas and water. This confirms that there will be some spill over effects following the loss of passporting rights to other parts of the economy as well.

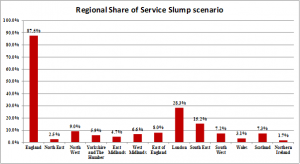

Regional Impacts of Service Slump Scenario

In previous work the regional impact of Brexit was outside of London and the South East. These two regions were relatively insulated from the difficulties that tariffs would bring to the goods sector.

This changes dramatically as a result of a service slump. London and the South East are now the worst affected areas. England suffers a more severe shock than Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Within England the South West is quite strongly negatively affected.

Chart 26

Source: Digit Ltd IO model

London is forecast to suffer an 8% drop in gross output following the service slump, which is a consequence of the strong regional concentration of financial services in the city. This would be in a similar range to the effect of the Gross Financial Crisis.

Chart 27 shows the share of the adjustment in gross output following the service slump.

87% of the adjustment is experienced in England. Around half of this adjustment is experienced in London and the South East. For many of the more northerly regions in England as well as in Wales and Northern Ireland, the impact of the service slump can be virtually ignored.

Chart 27

Source: Digit ltd IO model

Summary and Conclusion

Our analysis of a number of service sectors in the UK economy has shown that passporting of services with the EU is vital to the continued prosperity of many service industries. And it has also been established that parts of the service sectors are already adapting to the likely reality of Brexit, and even to the prospects of a Hard Brexit. This means that while the prospects for activity levels in financial services and insurance look relatively poor for Britain, companies involved in the industry may be able to find ways to continue to sell into the EU market by establishing subsidiaries on the European mainland that will continue to enjoy the full benefits of passporting. These benefits will not necessarily accrue to the British economy though.

Assuming that current demand conditions across the EU remain as they are, then a Hard Brexit could well lead to a change in the distribution of activities. Britain would lose some of its comparative advantage in financial services, and in some other services as well…

The ramifications of a disorderly Hard Brexit are likely to prove disruptive in many areas. They are likely to permanently affect the profitability of many areas, including the road haulage, air transport and financial services areas, including corporate and investment banking, and asset management.

It is possibly true that financial services may make “good” by expanding its reach outside of Europe. However, as with other trade areas, the UK would need to have exceptionally good relations with large markets such as China, the US and India, if the losses of business in the EU are to be fully compensated for. Not only are there no international trade agreements that cover services, the UK is currently exiting from one of the best international service trading arrangements in existence, namely the internal EU market.

The fiscal implications for government following the ending of EU passporting arrangements do not look good. As sectors experience reduced business volumes, so tax revenues will fall. Demands on government expenditure are likely to rise, and there is no Brexit Bonanza in sight.

Given stated government priorities, and a low growth/recession scenario, the government can only provide a counter-cyclical fiscal stimulus by either raising taxes, or by increasing borrowing, which break other election promises and “red lines”.

There are broader negative impacts on services following from a Hard Brexit. It will reduce EU support for R&D and technology, and reduce the attractiveness of our educational system to EU based foreigners. Being cut off from the Horizon programme will also weaken the UK’s role in international research projects. The ending of freedom of movement of people between the UK and the EU, one of the government’s red lines, will make it difficult to staff the NHS, and to find skilled employees for the financial services industry.

Indeed, it is striking to note how a series of poor decisions by the UK government has produced a set of “red lines” that rule out what otherwise might have been an inferior, but at least orderly arrangement, namely for the UK to become a member of the European Economic Area.

We started the paper by referring to the notion of a passport to nowhere. This appears to be the case at the moment (Quarter 4 2018). The government is handing in a passport that went somewhere in and with the EU, for one that goes precisely nowhere.

APPENDIX 1: LIST OF EU AGENCIES

References

Black A, et al “Hard Brexit, International Trade and the WTO Scenario”, Federal Trust, May 2017a

Black A “Hard Brexit and the Regions”, Federal Trust November 2017b

PwC, ‘Leaving the EU: Implications for the UK financial services sector’, April 2016,

Oliver Wyman, “T HE IMPACT OF THE UK’S EXIT FROM THE EU ON THE UK-BASED FINANCIAL SERVICES SECTOR”, (2016)

The Investment Association, “Beyond Brexit. A new Partnership with the EU for the Asset Management Industry. June 2018

Deutsche Bank, “Brexit impact on investment banking in Europe”. July 2018, Deutsche Bank Research

Vincenzo Scarpetta, Stephen Booth, “How the UK’s financial services sector can continue thriving after Brexit” Open Europe, 2016.

City of London Corporation Research, PwC, “Total tax contribution of UK financial services”, Nov 2017

Andrew Gray, Nick Forrest, Jonathan Gillham, Jing Teow, Edmond Lee, Jinny Park, “Impact of loss of mutual market access in financial services across the EU27 and UK”, PwC , 2018 February

Prof. Dr. Christos V. GORTSOS, “Potential Concepts for the Future EU UK”, FCA, London, 2016

Dirk Schoenmaker, “The UK Financial Sector and EU Integration after Brexit:” Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, 2017

The Boston Consulting Group (BCG), “Bridging to Brexit: Insights from European SMEs, Corporates and Investors”, (2017).

Pierre Reboul, Joseph Florentin, Matthew Weston, “THE IMPACTS OF BREXIT ON THE EUROPEAN FINANCIAL SERVICES ECOSYSTEM”, Eurogroup Consulting, 2017

Michaela Hohlmeier 1, and Christian Fahrholz 2,” The Impact of Brexit on Financial Markets —Taking Stock”, Deutsches Aktieninstitut e. V. 2018 (july)

Heidi Learner, “Financial Firms and Brexit: Where to?”, Savills Studley

HOUSE OF LORDS European Union Committee, “Brexit: the future of financial regulation and supervision HL Paper11th Report of Session 2017–19”, 2018 January