Chancellor Sebastian Kurz (centre), Minister Rudolf Anschober (r.) and Minister Karl Nehammer (l.) on 26th February 2020. Image copyright: BKA/Andy Wenzel

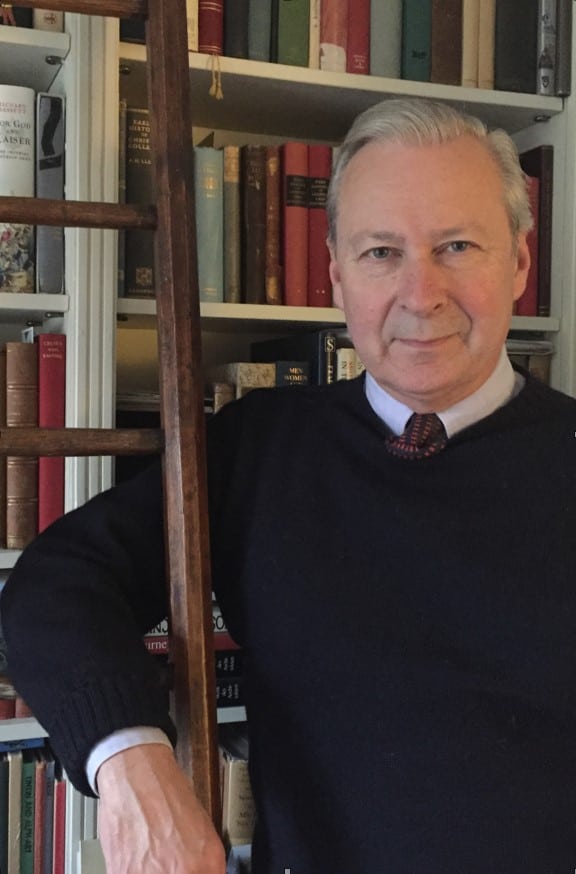

by Richard Bassett

Bye-Fellow of Christ’s College Cambridge and the author of “For God and Kaiser”, the first history of the Habsburg Army to be published in English (Yale 2015). From 1982 to 1991, he was the Central Europe Correspondent of The Times.

4th May 2020

George Bernard Shaw once wrote, with perhaps the memory of 1914 uppermost in his mind, “the most important bad news in the world is the bad news from Vienna.” Unconsciously echoing Shaw’s judgement, the popular German media in the middle of March chose to focus on the Austrian Tyrolean village of Ischgl as the source of “most German Coronavirus infections”. Initial German contact tracing had found that many of the first German victims had returned home recently from skiing holidays in and around the village. With “characteristic laxity” the “venal Austrian authorities” had permitted the popular ski-resort to continue “partying for days” after infectious cases had been traced to the village.

As a reprisal, Bild Zeitung urged shipments of vital medical equipment, notably masks, be prevented from entering Austria, and indeed, lorry loads of these supplies were, either for this or some political or bureaucratic reason, held up for days on the Bavarian frontier. At this stage, it looked as if Austria, despite the advantages of scale, was going to find it rather difficult to contain or even confront the virus with any degree of success.

Fast forward a little more than six weeks and as Austria has begun to lift its lockdown restrictions—-most shops have already opened and most restaurants will reopen in two weeks —, it has emerged as the “Musterschüler” (exemplary pupil) of the “School of Europe” in its approach to the virus.

As of May 1st, there have been, out of 15, 531 known cases of infection in Austria, only 589 deaths. Of the 15,531 known cases, an impressive 13,110 have already recovered. Testing and contact tracking and tracing have resulted in large swathes of the country emerging after lockdown and a strictly enforced quarantine “virus-free”. In the province of Salzburg for example, 81 of 119 districts were last week declared to be without any suspected cases of the virus. Of the 145 known cases in the City of Salzburg, 130 had recovered by May 1st.

Such figures cannot entirely be explained by the structural advantages of a small country with a well-funded health service, although such advantages, especially in terms of capacity and equipment, the result of political decisions over many decades, are not to be underestimated. What is striking in the Austrian statistics, however, is the way in which they reflect a coherent, transparent strategy which once formulated by the country’s political leadership moved relatively seamlessly along a route of clear milestones to deliver what many scientists agree has been so far the most effective suppression of the virus observable in any European country.

It helps that Austria has one of the most illustrious medical traditions in the world. Not just Psychoanalysis originated in Vienna. Percussion diagnostics were first discovered and deployed in 18th century Vienna by Leopold Auenbrugger. The now all pervasive and virtually obligatory frequent washing of hands was the nineteenth century innovation of another Austrian physician, Ignaz Semmelweis. Tradition and infrastructure alone, however, are useless without informed political direction.

To the surprise of many outside observers, and even many Austrians, the Austrian government took a number of decisions which after the initial “Ischgl debacle” demonstrated a determination to grip the challenge with all the means at its disposal. The first, and perhaps on reflection most important decision, was to see the threat the virus posed in starkly realistic terms. At the beginning of March the temptation to underestimate the threat was widespread. Scientific advice comparing it to the annual bout of influenza proved particularly misleading. Given the very low incidence of known cases in Austria by the end of the first week in March there was certainly little incentive to treat the virus as anything more than a manageable threat requiring few exceptional measures.

However, the Austrian Chancellor, Sebastian Kurz decided to evaluate the outbreak more seriously. In reaching this decision he received some significant external help. On March 7th with only 81 reported cases of the virus in Austria, the Chancellor took a late-night call from the Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. For those who recall the almost total breakdown in relations between Austria and Israel in the wake of the election to the Austrian presidency of Kurt Waldheim, thirty-five years ago, such a call in itself is worthy of note. It would have been inconceivable then and in its own way nothing illustrates more vividly the progressive path Austria has successfully navigated over the last three decades than this simple telephone call.

Netanyahu had a helpful message to impart, one which the Chancellor would later recall “made me sit up straight and not sleep a wink that night.” The Israeli prime Minister’s warning was simple: “Do not underestimate Coronavirus; it is not the flu and it is going to hit Europe extremely hard. Wake up and take action!” At that time Austria was still permitting mass gatherings. Social distancing was an abstract concept, but the Israeli warning had its effect and within a week, by March 15th , Kurz had banned all gatherings of more than five people, closed all businesses, restaurants and shops. The lockdown which followed was rigorously policed, sometimes with an excess of zeal, much to the annoyance of the Viennese who found themselves suddenly prohibited by policemen from even resting on a park bench when they took their dogs for a walk. Generally, however, public acquiescence in the new measures was widespread and the restrictions were accepted as the necessary price to pay in order to contain the virus.

The Chancellor regularly (but not daily) updated the country on the efficacy of the latest measures, cleverly avoiding promises which could not be kept, fatuous predictions and poorly concealed half-truths. While he welcomed scientific input, he made it clear that political responsibility and decision-making would not be subordinated to the contradictory speculation of unelected scientists. As the crisis developed, he rather skilfully offered glimpses of a way out of the restrictions without tying himself down to any rigid timetable. When in future, political scientists examine the responses of European political leaders to the coronavirus crisis, Kurz’s strategic response may well be seen as a textbook example in Political Studies faculties throughout the world.

It helped that the Austrians proved largely biddable, complying with the restrictions with a mixture of discipline and resignation even as entire communities and villages were in some cases quarantined strictly for several weeks. The ski resort of St Anton, the most popular annual destination for English tourists in Austria, found itself for weeks sealed off from the rest of the country following the discovery of a handful of cases in one of its outlying districts.

Paradoxically, these stringent measures did not shut down all commercial activity. Austrian confectioners looking forward to the busiest season of the year (Easter), far from ceasing their activities, as in many other European countries, actually operated within the restrictions to preserve their sales, supplying chocolate eggs to clients in Austria and even the rest of Europe where customers were grateful for the chance to replenish domestic supplies which had vanished despite less stringent lockdowns.

Today, as the commercial restrictions end gradually in Austria , the eyes of the rest of Europe might do worse than focus on how the Austrian experience appears to demonstrate that something approaching the “status-quo ante” is perhaps not as wildly remote as many fear. Austria may well offer a template for how to phase the recovery of the hardest hit industries, notably hospitality and tourism, both key components of Austria’s economy. It will be vital to stage their reopening in a measured way. Austria’s lessons as they undertake this challenge will not be without interest to other countries, even larger European states such as France, Germany and the United Kingdom.

The British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, on his return to the daily briefings of the media in Downing street appeared, predictably, rather defensive when asked why the United Kingdom’s mortality and recovery rates compared so unfavourably with the rest of Europe. It was “too early” to make any “meaningful comparisons” with other countries, he insisted. His Chief Medical Officer repeated and expanded this clearly carefully choreographed answer, noting that lessons were being “learnt by all countries all the time”. The faintly incestuous compliance of the British media with these patent banalities should not distract us from examining other European countries’ experiences.

One understands the reluctance of the Prime Minister to compare the British record with those of other European countries such as Austria. The intellectual crippling which Brexit imposes on the government allows little time or space for a realistic evaluation of European conditions. At the same time, if comparison is the basis of all analysis, then the findings of such an exercise are unlikely to bestow equal praise. Nevertheless, an examination of Austria’s record in dealing with the crisis is illuminating as to the advantages of transparency, coherence and above all intellectual honesty. These are qualities which will no doubt continue to stand the Austrian political leadership in good stead as they navigate their way out of the virus-imposed lockdown. The “light at the end of the tunnel” to which the Prime Minister referred is undoubtedly the good news from Vienna.