Anyone hoping the US under President Biden will restore its own democracy to the level at which it could be an example for most of the world, must be quite disappointed. Even deeper disappointment must be felt by millions of anglophiles who were looking towards Britain as a gold-plated model of democracy. British nostalgia for the lost empire was perhaps the key factor behind Brexit. It was also driven by a strong anti-Europeanism among political elites based among others on the belief that British democracy being the oldest one is also the best, as is its electoral system. This is one of the key differences between the European and the British model of the post-war democracy. In Europe, a proportional voting system produces mostly coalition governments, whereas the UK governments, elected using the First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) system, have been run almost exclusively by a single party.

British politicians stick to the belief that ‘strong’, one party rule, is more efficient and more effective in delivering better quality of life for the British citizens. After all, they may think, the main objective of governments in a liberal democracy is to deliver the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. That is why some politicians supporting Brexit have argued that once the constraints put by the EU are removed, Britain will become a much stronger economy. However, if we measure the quality of life by GDP per capita, the actual results do not confirm that a single majority party elected using the FPTP system delivers ‘greater happiness’ than the coalition governments in Europe elected using a proportional voting system. For example, in 1989, the GDP world rank per capita was: in the UK – 17, Germany – 20, France – 24. In 2019 the UK’s rank was 37, Germany’s – 26 and France’s – 35. This means that in the last 30 years the UK’s world ranking in GDP per capita fell by 20 places, whereas for Germany, which had to absorb in that period 17 million of East German citizens fell by just 6 places, and for France by 11 places.

The biggest disadvantage of a single party government seems to be the adversarial nature of politics as has been evidenced so plainly during the UK’s Brexit proceedings in the Parliament. The adversarial politics based on the majority of MPs of a single party, which does not have to win the majority of the votes to rule the country, leads by extension to a deep polarization of a society, which was so characteristic of the Brexit campaign.

Additionally, such an adversarial politics suppresses by its very nature the inflow of new ideas by virtually eliminating smaller parties in the FPTP system. The voters have less choice and therefore quite often either do not vote at all, or vote tactically, which only rarely delivers the intended result. The whole focus of the government is on winning the next election by tuning the ruling party’s manifesto to temporal whims of the electorate. Once the votes have been cast, voters cannot rectify bad laws passed by the parliament, nor can they demand passing new laws, inconvenient for the government in power. However, irrespective of an electoral system, it seems that the real root cause of the current crisis of democracy originates from four types of imbalances:

- The lack of balance between the rights and responsibilities. The overwhelming focus on human rights has created an unhealthy imbalance by barely mentioning the importance of responsibilities in maintaining social cohesion.

- The lack of balance of power between the majority and the minority, which Alexis de Tocqueville called the Tyranny of the Majority. That undermines the foundations of the liberal democracy, perhaps best expressed by Jeremy Bentham – ‘creating the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people’. The only solution to solving this problem seems to be disallowing a single party government, even if they have an absolute majority. Instead, coalition governments with the Head of State as a conciliator may be a better solution.

- The lack of balance of power between the central and local government, which in some countries, such as Britain has been stifling social and economic development. True citizens’ engagement cannot happen without a deep decentralization of power.

- The lack of balance between the power of the voters and the elected representatives. One reason why democracy has been eroded is the inability of the voters to have a continuous oversight through their randomly selected delegates over the legislation and decisions made by the parliament.

It is that last imbalance between the power of the voters and the governing, which should become the starting point of a deep reform of democracy because it would directly limit some excessive powers of politicians. The best way to achieve that might be by merging representative democracy with direct democracy. Thus, a new type of democracy would be created, which might be called Consensual Presidential Democracy.

So, how can we merge representative and direct democracy? In recent years, there has been a growing support for a new political decision-making body called a Citizens’ Assembly, to which delegates have been randomly selected in a similar way as in the ancient Greece. They are generally focused on specific political issues, such as electoral reform or gay rights. There have been over 250 Citizens’ Assemblies worldwide covering various political topics. Perhaps the best testing ground for their applicability is the current Conference on the Future of Europe, which is to deliver its recommendation in spring 2022. The Conference’s agenda includes 10 Topics debated by National Citizens Assemblies, to which delegates have been randomly selected from all EU countries. Each such a National Assembly selects then delegates to the European Citizens’ Assembly, part of the Conference Plenary. If the final result of the Conference broadly follows current proposals, then it may be converted into a de facto Constitutional Convention.

Although Citizens’ Assemblies are not a silver bullet solution, they could help correct some deep fault lines in the current democratic system and bring to democracy two very important elements: neutrality and diversity. However, to have a real and continuous impact on politics, they should become a permanent part of a legislative system at every level of a new democracy, giving citizens a continuous real influence in political decision-making.

From Citizens’ Petitions to a Citizens’ Senate

The first step towards a continuous oversight of the elected politicians might be a system of citizens’ petitions, which already exists in some countries. For example, in Britain in 2015, a formal on-line petition system was introduced. However, out of over 50,000 petitions filed in the last 5 years, only one new law was passed – on removing tax on tampons. So, petitions, at least in Britain, are a frustration valve for the voters and a fig leaf for the governing party, covering the current system of total power grab after the elections. Therefore, we need a different, ‘reinforced’ petition system, but in which a higher level of support e.g., of 5% of the eligible voters would be required.

Such a petition system would be the first stage in merging representative and direct democracies. Its key function would be to trigger the calling of a Citizens’ Senate session. In this way, it would be the citizens’ who would have the right to initiate its individual sessions to discuss a certain problem, rather than the parliament.

The main reason for having such a bicameral system is that elections and a random selection each offer a different type of representation. In an elected chamber, the aim is to have representatives who would consider the needs of the entire population. By contrast, in a Citizens’ Senate, randomly selected members represent themselves and therefore they have substantial independence in the voting preference. Both points of view are valuable and would result in a much better fulfilment of what a given nation really wants and how it wishes to be governed.

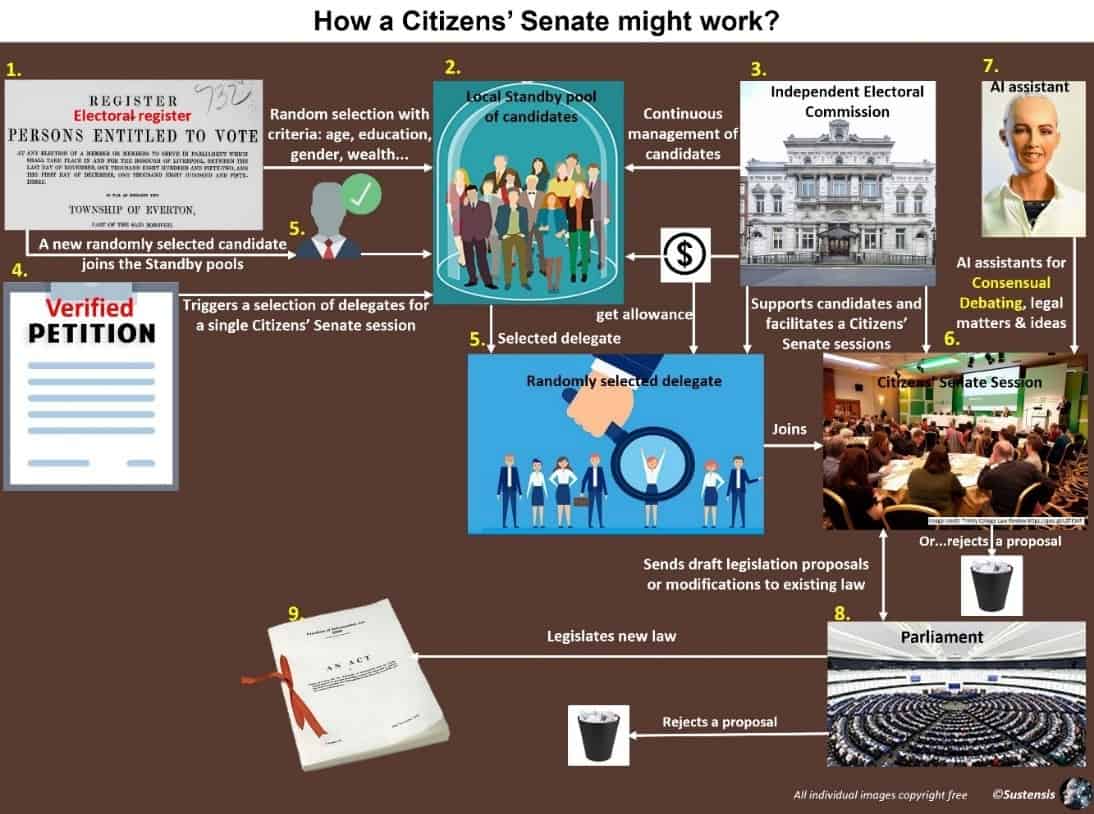

A Citizens’ Senate session should consider only one issue to avoid lobbying pressures. For each such session, a new lot of citizens would be randomly selected. Once Senators have passed a resolution, a session will be closed, and the delegates will complete their service. Here is an overview of how a Citizens’ Senate might work.

An overview of how a Petition system, a Citizens’ Senate and the parliament might function

An overview of how a Petition system, a Citizens’ Senate and the parliament might function

In summary, a petition system linked to a Citizens’ Senate seems to be the most logical starting point. Decisions of the Senate, with appropriate legal assistance, would have the power of a draft legislation. The parliament could only reject it with a qualified majority. If it could not agree on modifying the presented draft legislation within one year, such a legislation would automatically become law. That seems a simple and fast track way for the citizens to share the real power of governance with politicians.

Such a new model of democracy will significantly re-engage citizens, maintaining a continuous accountability of the governing to the governed. A Citizens’ Senate would become the bridge merging representative and direct democracy. In such a democracy, only coalition governments would be allowed, with the President playing a pivotal role in achieving broader than ever consensus. To increase such a consensus even further, the leaders of the two largest parties would have the role of Vice-Presidents. Such a Presidency would then be both more representative of the entire nation as well as capable of making swift, unpopular decisions in emergencies.

Leave A Comment