by Bob Savic, Senior Research Fellow at the Global Policy Institute and an advisory partner with Petersburg Capital LLP in London.

6th March 2018

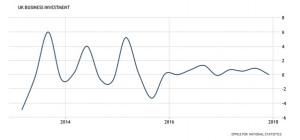

For about two years (i.e. from December 2015 to date) corporate investment in the UK economy has been growing at or around 0%. This is an unprecedented slump in business spending.

Looking back at data going back to the 1960s, there has never been such a prolonged slump in UK business investment. Typically, such investment is highly cyclical, so that it rises over six months and then falls over six months, on an annualized basis, every year.

This half-yearly trend was interrupted somewhat in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) when investment plummeted by nearly -8% annually – over a twelve month period – from mid-2008 to mid-2009. However, it rebounded strongly to hit 6% growth in the first quarter of 2010, mainly due to a re-activation of deferred business investment plans arising from the GFC.

Notably, in the six months leading up to the EU referendum, in June 2016, and thereafter, investment has been flat, and the usual cyclical trends described above have simply evaporated. This unprecedented period of near zero investment growth can only be attributable to the uncertainty surrounding Brexit. Not even the supposed Armageddon-like consequences of the GFC, several years earlier, have made such a lasting impact on UK business spending.

UK Business Investment

As long as this glaringly evident economic phenomenon is ignored, or its implications misunderstood, then the negative long term consequences of Brexit will impact the UK’s economic fortunes through stealth rather than a one-off sudden shock (recall doomsayers predictions of an immediate post-Brexit vote economic slump that failed to materialise!)

Arguably the latter would have been cause for a rude wake up call that may have galvanised the political establishment to reverse Brexit. Unfortunately, because the former is less visible, there will likely be more long term negative consequences for the UK economy, unless the political establishment begin to act resolutely in dealing with an untold crisis in UK corporate investment which is evidently flowing through into declining headline economic growth.

UK GDP Annual Growth Rate

By contrast to lacklustre UK corporate investment, Britain’s export sector has been booming, of late. Yet, contrary to Brexiteers proclamations that non-EU markets is where all the action is, exports in December 2017, being the last month of recorded trade data, rose to the EU by 6.9%, particularly to Germany (17%), France (22%) and Ireland (2.3%).

Interestingly, exports to non-EU countries fell -3.6% overall, including some of the Brexiteers’ favourite destinations for future export growth, such as China (-27.4%), Hong Kong (-30.4%) and South Korea (-20.3%).

But if the UK leaves the Single Market and the Customs Union, as appears to be Prime Minister Theresa May’s ambition, Britain may soon start to see EU exports slump as much, if not more, than corporate investment.

According to the National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR), should the UK leave the EU’s single market, and managing to substitute it only with a Free Trade Agreement (FTA), which was the EU’s chief Brexit negotiator, Michel Barnier’s immediate response to May’s speech calling for a deep and comprehensive partnership, then the long term fall in goods trade could be as much as -35%, from current levels. For services exports this could plummet by as much as -61%, since an FTA would not compensate for the loss of non-tariff barriers inherent within the internal market.

And if that’s not enough, there would also be the loss of trade from Britain losing access to third countries’ FTAs with the EU. This is because, post-Brexit, the UK would cease to be party of these agreements, unless the partner countries extended their FTAs to the UK, albeit subject to resolving a range of complexities, as well as being historically unprecedented.

Currently, the EU has 34 FTAs, nearly 50 part-concluded FTAs and partnership agreements (including with Canada) and four pending-signature FTAs including with Japan, Singapore and Vietnam.

Given that China and India, in respect of which Theresa May and Boris Johnson led high-profile business delegations, respectively, showed no interest in starting FTA talks with the UK (mainly because their prime interest is in concluding FTAs with the EU), the potential loss of trade privileges from exiting the single market and the customs union, will be even more devastating than just the potential loss of trade with the EU itself. To top it all, it may well be decades before the UK can even achieve the number of FTAs it currently has through the EU, let alone negotiate new FTAs, given the painfully slow nature of FTA negotiations and their ultimate ratifications.

If Brexit was supposed to herald a “global Britain” built on free and open trade with the rest of the world, according to the Brexit mantra, then very little of that political bravado seems to have spilled over into the business coffers and sales departments of those that actually do the trading – Britain’s companies and entrepreneurs!